“… that most deathly day “

Edmund Blunden Pillbox

The Battle of the Somme had begun on July 1st 1916, after a week long bombardment when over a million and a half shells were fired on the German trenches. Tens of thousands of men on an eighteen mile front amassed for the `Big Push’ which would end the war. By nightfall on July 1st the British Army had suffered over 57,000 casualties; killed, wounded and missing. Aside from a few small gains around Mametz and Montauban to the south, the Big Push had withered in the face of uncut wire, stiff resistance and German machine-gun and artillery fire.

By September 1916 the success in the south had been exploited, and the fighting had moved on to a number of woods which soon became household names; Mametz Wood, Trones Wood, Delville Wood, High Wood. Division after Division were thrown into the tumult. Further ground was gained. German positions were taken. Counter-attacks fought back. Casualties continued to mount.

One part of the line that was proving a particularly tough nut to crack was Thiepval. Situated on high ground, flanked by the well prepared defence works of the Schwaben and Stuff redoubts, and overlooking Thiepval Wood and the Ancre Valley, it loomed down on the British troops. It’s prominence precluded any further operations in this sector. Therefore it had to be taken.

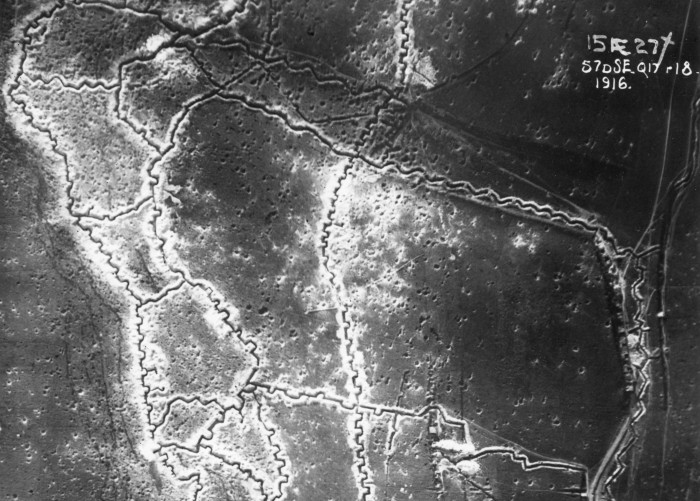

The attack at Hamel was part of one such attempt to break the fortress of Thiepval. As part of V Corps, IV Army, the 39th Division were to attack north of the Ancre from Hamel to just below Hawthorn Ridge. South of the Ancre, the 49th (West Riding) Division were to make their assault on the Schwaben Redoubt and Thiepval village. Zero hour was set for 5.10am, and the attack would be preceded by a swift but heavy artillery barrage, using artillery brigades not only from the 39th Division, but others on loan from two other divisions. The general objective was to push on from the German front line, over the Ancre Heights towards Beaucourt, some miles distant. At the same time, it would also relieve the pressure on the main attack on Thiepval.

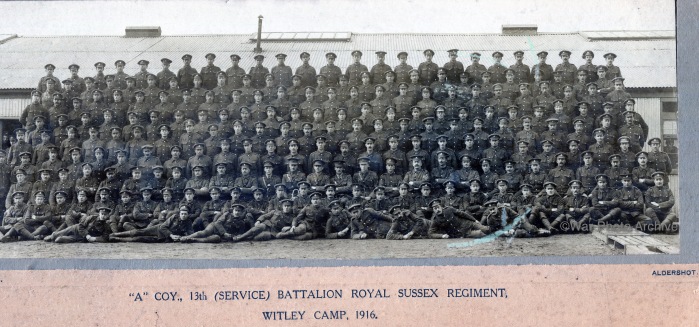

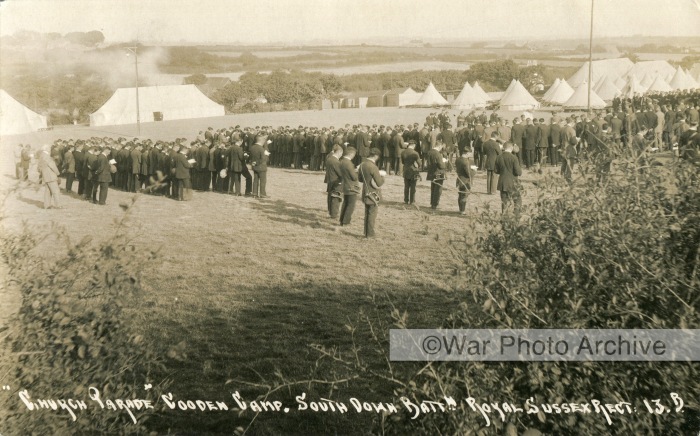

By the time the Southdowns arrived on the Somme, operation orders for the attack had already been formulated; only the final matter of exact map references and timings had to be added to a plan worked out at Monchy-Breton. Headquarters of the 39th Division detailed 116th and 117th Brigades to spearhead the attack, with 116th Brigade in and immediately east of Hamel village, and 117th in the valley to the left. In 116th Brigade Hornby looked at the fighting strength of his battalions and found only the 11th Royal Sussex and 14th Hampshires in a position to lead the attack on their front. Even so, the 11th had only 530 all ranks, and the 14th Hampshires 570 men. The 12th and 13th, although in receipt of various drafts after their blooding at Richebourg, were still terribly under strength and so they were designated to play a reserve role in operations.

The operation orders handed down to the attacking battalions laid out the fine details of the operation, designated for the early morning of September 3rd 1916. The 14th Hampshires would advance on the left, and the 11th Royal Sussex on the right, with the 13th Battalion in reserve behind. The 11th Battalion’s first objective was detailed as the German front line immediately north of the Ancre Valley; from there they would push on to the second objective in the support line, and follow this with an advance on the third and ultimate objective which was a maze of German trenches over the high ground, guarding the approaches to Beaucourt-Hamel railway station, further up the valley. The 14th Hampshires attack was to be in co-operation with this, capturing the German lines further along from where the 11th Battalion would advance. The 13th Battalion would be on hand in a support role, with the 12th Battalion in Hamel village and rear positions known as `Kentish Caves’ and act as a ready reserve. Due to the fact that they were now down to only 270 all ranks, it was hoped they would not be used unless a real emergency arose.

Supporting the attacking battalions were sixteen Vickers machine-guns from the 116th Machine Gun Company MGC, and eight 3″ Stokes mortars of the Brigade Trench Mortar Battery. Four of the Vickers guns each would accompany the 11th Royal Sussex and 14th Hampshires into the attack, and be at their disposal to establish strong points to provide cover fire once in the German trenches. The remaining eight guns would provide a machine-gun bombardment, now more and more common by this stage of the Somme battle, firing on German communication and support trenches, along with the approaching roads from Beaumont-Hamel to the north and Beaucourt-Hamel to the east. The Trench Mortars were to establish themselves in or near the front line, and accompany the attackers if required by the commanding officers of those battalions.

The artillery support was in the form of several batteries of eighteen pounders, a number on loan from other Divisions. Some would fire shrapnel to cut the German wire, while others would bombard the positions with high explosive to create as much damage and mayhem as possible. Lessons had been learnt from July 1st. No long preliminary bombardment would preceded the attack; Heavy Artillery groups of the Royal Garrison Artillery would initially engage their guns on the positions to be attacked, and gradually the Field Artillery would take over and keep up a steady barrage on pre-designated targets, on the lines of those outlined above. The artillery plan itself was no-where near as rigid as that exercised on July 1st, and Batteries could be called back to selectively fire, on the request of those commanding the attacking infantry battalions. Communications between the artillery and infantry were now seen as the key to a successful operation, and every effort was made to keep these lines, either in the form of runners, pigeons, flares or telephones, open throughout the operations. Indeed, each of the battalions in 116th Brigade was assigned an Artillery Liaison Officer who was to co-ordinate communications during the battle. With them they would have sections of trained artillery signallers, and extra telephone equipment and the tools to repair the line which all too easily became cut by hostile shell fire.

Within each attacking battalion, the various companies would `leap frog’ their way across the objectives, with two companies capturing the first objective, the other two moving on ahead of them to the next objective, and so on. Mopping up parties would left at each objective to clear the trenches of any Germans taking shelter in dugouts or saps; again a lesson of July 1st, when many attacking Divisions had paid scant attention to this, resulting in Germans coming out of their positions and firing on the attackers from behind.

The troops themselves would not go into action laden with equipment, again as had been the practice on July 1st. Each soldier adopted fighting order, without his large pack and greatcoat. He would also carry two Mills hand grenades, two sand bags and a hundred rounds of extra small arms ammunition. The unused proportion of the day’s rations would be taken in the small pack, along with one iron ration and a full water bottle. A good hot meal would be provided on the morning of the attack, and Rum would be issued prior to zero hour.

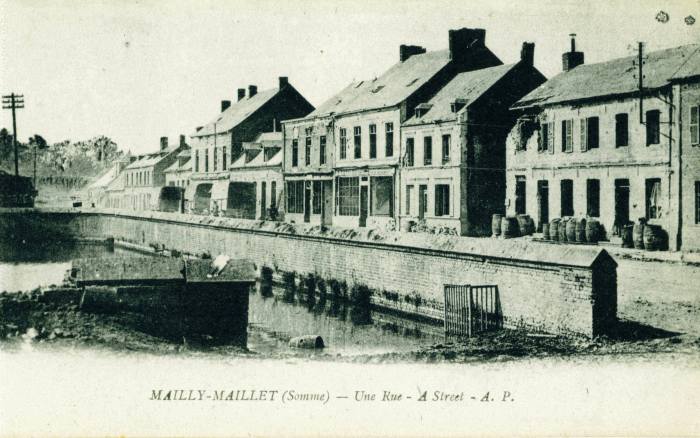

The final days prior to the operation were spent in billets at Mailly-Maillet. Corporal William Booth had been detailed to be part of one of the mopping up parties,

“… I was to be responsible for clearing any dugouts on our front. I could select any six men I wanted. As I did not relish going down steps with a rifle and bayonet, I asked for, and was issued with, a revolver and 50 rounds. I got permission to fire 5 rounds in practice.”

Booth’s elder brother, Frank, was also serving in the 11th Battalion and during their recent stays at Mailly, Booth had seen little of him. Being in his company’s bombing section, Frank had been busy making forward dumps of Mills grenades. The brothers took this all too brief respite as an opportunity to meet. Booth remembered, “… we wished each other a whispered good luck ” (Booth).

One final problem arose in the days leading up to the attack at Hamel. A wide gully lay between, with banks at either sides ten to fifteen feet high. Poor weather had made the ground in the gully quite muddy, and there were fears the men would have difficulties in both coming down the banks on the British side, and climbing the ones nearer the Germans. Wooden ladders were therefore constructed by the Divisional pioneers, and brought down to the trenches. Booth, and several other men in the 11th Battalion, were given the job of taking them out prior to the main operations. They went out in the darkness and,

“… our task was to collect the ladders and put them in the gully, trying to cover them with any grass we could find. Personally I did not like the look of things and did not feel very happy about our chances.”

Back in Mailly final arrangements were made. Booth was back with the battalion, as they assembled for the journey to the trenches. As they left the village, there were calls of “Good luck mate, see you in Berlin”. The troops they relieved in the line were tired and pleased to see them, having spent the previous days tearing down sandbags and piling them up in the bottom of the trench so that it would be easier to exit at zero hour. The night passed quietly, and at 4am on the morning of September 3rd dixies full of coffee arrived. Officers and NCOs added rum to the enamel mugs being passed round. Booth recalled, “… after the rum, we all felt better and were longing for zero hour”.

Zero arrived at 5.10am. The artillery support laid a intense bombardment on the German front line as the attackers left their trenches. This barrage moved to the support lines five minutes later, and then to the reserve lines until called back during the operations.

On the 11th Battalion front the men left their trenches in good order and advanced in extended order across No Man’s Land. Booth was among them.

” We all seemed to have survived the first move, and it was now just starting to get light across the gully and no sign of the ladders we had so carefully stowed there… we [could] only think Jerry found them and carried them off.

We were now faced with the task of climbing this bank without ladders. I shouted to the men to help each other, but cannot believe it was heard. I managed to get to the top myself, and had just placed my rifle on top when I slipped down and had to go up again. This time it was a bit easier without my rifle and looking right and left I could see most of the platoon were up…

As we moved there was a sudden silence. The barrage had lifted and we now tried to run, but before I could get to the trench… I caught my foot in the wire and went down with a bang. I got up and literally fell into what had been the trench.”

The Germans responded quickly with a bombardment on No Man’s Land which seemed to grow in intensity and caught many in the waves behind Booth, still struggling to climb the gully. Terrific fighting now took place in the front line trench; Sergeant Booth and his comrades were in the thick of it.

” I jumped up to try and see where Jerry was and saw tops of helmets, told the two with me to follow me, had my revolver in left hand, threw a Mills grenade over into what I hoped was their piece of trench and before this exploded there was a terrific explosion behind me – I was thrown off my feet and I could feel my legs were wounded. I just got on to my knees when I saw German boots beside me.. he brought his rifle down on my head with a terrific crack. Before he had a chance to do more I poked my revolver into his belly and he fell on top of me.”

Booth had caught the blast of a German stick grenade. He only knew this much later, when parts of it were removed from his backside while in hospital at Etaples. His two comrades had gone, so he crawled on a bit further into a bay where he found another wounded 11th Battalion man.

” I pulled myself up to look back to our trenches. Troops were still coming up out of that awful gully. Now 30 yards away was a Jerry MG with a crew of three firing at them. I slipped down into bottom of trench hoping they had not seen me, decided then I could try to stop them firing; found a rifle that worked, got myself into position where I could push rifle over top, take aim and fire, but I must have been seen and did not know another Stick Bomb had been thrown at me… I was blasted down into bottom of trench again. It felt as though the right side of my face had been blown off and my right arm was bleeding and blood was coming from my mouth.

Suddenly on top of the trench appeared a Capt Northcote – OC C Company. Those who survived were going on to the next objective. He at first shouted at me to get going, then saw that I was helpless and collected any Mills he could find. He no sooner climbed out of the trench than he was shot, I expect by the MG crew, I could still hear [them] firing.”

Meanwhile, officers like Northcote had been trying to make sense of the situation. The men Booth had seen back in the gully were those from the fourth wave under Captain C.L. Mitchell. Seeing what had happened to the preceding three waves, Mitchell initially held his men back as by now the German barrage on No Man’s Land was terrific. He ran out into No Man’s Land alone to assess the situation, and returned leading his men forward to the gully. Despite casualties, many of them reached the German wire, where Mitchell ordered them to dig in and form a defensive line against counter -attacks by joining up shell holes to make a new trench. This eventually proved to be a dangerous position, as shell after shrapnel shell fell on Mitchell and his men, inflicting heavy losses.

At Brigade Headquarters, Brigadier General Hornby noted,

“… the heavy hostile artillery fire… and the continuous machine-gun fire from the south side of the valley of the river Ancre, made it difficult to get up reinforcements.”

It was reports like this that made battalion commanders such as Lieutenant Colonel G.H. Harrison re-assess the situation. Harrison was a regular army officer from the Border Regiment, who had seen active service elsewhere on the Western Front. He had officially taken over from Grisewood soon after Richebourg. Sending Second Lieutenant Edmund Blunden forward to gather more information, Harrison soon concluded that continue with the fighting was pointless. He also understood that the 14th Hampshires on the left had encountered similar problems, and that the 117th Brigade had totally lost direction. Through Blunden, orders for a withdrawal were passed down. Mitchell organised his men, and although heavily strafed on the way, he managed to get most of them back.

Left behind were many dead, wounded and dying. Among the wounded was Sergeant William Booth, who while attempting to return to the British lines had been wounded a fourth time with a bullet through his leg. He had been joined by another wounded Southdowner but realised he was in a bad way; “… all through the day shells had been dropping all round and at times I wished one would drop in, for the heat and pain were awful” (Booth). Booth passed the night in his shell hole in No Man’s Land, until discovered the next day by a friend in C Company.

” He tried to stand me on my feet. They were the only part of me not wounded. I just could not stand so he got me up on top, then on his back as he lay on the ground, then tied my hands together in front of him and then he started to crawl. What a hero he was – he could hear both German and English voices as there seemed to be some sort of truce to help get the wounded in.

He dragged me to the edge of the gully and somehow managed to lower me down. He must have been just about all in, but he assured me he would be back. I don’t know how long after, but he came with one of our own stretcher bearers but no stretcher. They carried me somehow and got me up the other side and then into what had been our own front line.”

From here Booth was slowly evacuated down to the battalion Regimental Aid Post, and from there to a Field Ambulance via a wheeled stretcher. After that he was taken to a Casualty Clearing Station by ambulance. He knew he had a `Blighty One’ and that he was going home, but even here, Booth ran into problems,

“… an orderly of the R.A.M.C. came and said he had got to remove all my clothes. First thing he did was cut off my respirator. I told him to be careful as there were some detonators in it. He almost ran away and came back with a C.S.M. who threatened to put me on a charge for bringing them into a hospital.”

Elsewhere, the 13th Battalion had run into similar problems. Like their comrades in the 11th, a welcome issue of coffee and rum had arrived before zero hour. Although in a support role, the whole battalion had already been detailed to follow the 11th Battalion’s attack, and so at zero hour they moved off into No Man’s Land. A and B companies spearheaded the attack, and encountered the same difficulties in crossing the gully. At one point, due to the intensity of the German barrage, many men took shelter in the gully. This proved of little use as cover, so the officers ordered their men forward again. By the time D Company reached these positions, all the officers of C Company had become casualties. The officer now in charge, Second Lieutenant H.H. Storey, sent one of his officers to find out what was holding up the advance. This Second Lieutenant encountered Captain Mitchell of the 11th, who told him he could, and would not, advance unless ordered to do so by his commanding officer. This order having not been given, Storey ordered his men in support of what was left of the 11th Battalion, who were by now storming the German support lines.

However, as they left the partial cover of the gully, they came under murderous machine-gun fire, with several officers being wounded, and resulting in Story’s party falling back again to the gully. But, with the aid of some stragglers, Storey pushed forward yet another attack, and after losing direction somewhat ended up in a very battered German trench. He decided to hold on to this precarious position, and sent out patrols to see what was happening and make contact with the rest of the battalion, but to no avail. One last patrol returned with the news that a withdrawal was taking place among the 11th Battalion, so Storey led his men back to the original British front line. Here he was sent down to the commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Draffen, who told him he had information that elements of the 11th were still in the German lines, and so Storey and his men would have to attack again. However, orders came down from Brigade Headquarters at the last minute, saying the attack was over and Storey was to stay put.

Meanwhile, A Company under Captain Arthur Fabian was making its way towards the German front line; but not before they ran into a dazed mob of stragglers from the 117th Brigade who informed them the order to withdraw had been heard. Fabian ignored them, and led his men on with the call ” Come on A Company 13th ! “. Fifty yards from the German trenches Fabian had two of his fingers blown off and although continuing to lead his men, he finally went down in a hail of machine-gun fire. All momentum was now lost, and the survivors took cover in shell holes. At this point, the only officer left, Lieutenant John de Carrick Cheape, took over what was left of the now disorganised and scattered Company. By now, the only worthwhile job left doing was to collect the wounded, it was while helping with one of these stretcher parties that Cheape, too, was hit and killed by a German sniper. Leaderless, the survivors made their way back to the British lines.

The support troops had faired little better. The Vickers guns had failed to come into action, as none of the positions captured could be consolidated. The 116th Trench Mortar Battery officer could only report heavy casualties in his unit and that the best his unit had been able to do was set up two Stokes mortars in a shell hole in No Man’s Land and fire 260 rounds in support of the infantry. The officer in command of them, Second Lieutenant F.W. Barrow, a Southdowns officers attached, lay dead near the guns.

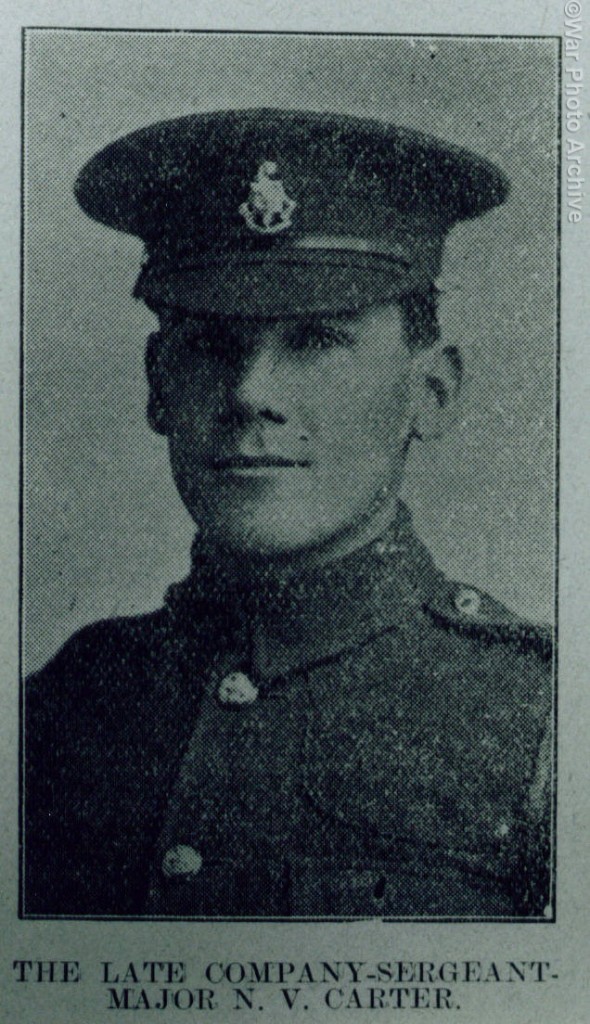

Casualties had been high. In the 11th Battalion had lost ten officers and 296 men; of the latter 105 appear in Soldier’s Died, showing a high fatality rate. In the 13th Battalion, 11 officers and 128 men were killed, wounded or missing, which amounted to over a third of their fighting strength. Their medical officer, Lieutenant Dunning, had been among the casualties; wounded bravely risking his life tending to the wounded in No Man’s Land. As at Richebourg, many of the dead were left behind in the German trenches, and a large number of wounded were taken prisoner; among them Second Lieutenant C.A. Vorley, who died of his wounds ten days later in a German field hospital.

The attack had been a failure, as likewise in the 117th Brigade, the German trenches had been entered but not held. Too many men had become casualties while crossing No Man’s Land. The German wire had been well cut, but the artillery had failed to silence machine-gun units holding out in well constructed, deep dugouts. The ability to call back the barrage had proved limited, despite the extensive planning as far as communications went, but the terrific German bombardment across the gully had made it almost impossible to keep any telephone lines open. Major Neville Lytton, a former 11th Battalion original, was on his now usual duties as a staff officer with the 116th Brigade Headquarters. He came to the conclusion that the operation at Hamel was part of the costly learning process the British army was going through on the Somme. He wrote,

“… another good day for the Germans, I fear; the truth of the matter is that they had such wonderful defences our artillery fire had not broken the morale of the defending troops, and the situation was not yet ripe for an infantry attack.”

A similar fate had befallen the 49th (West Riding) Division on the other side of the Ancre; they had likewise failed in all their objectives, and the murderous crossfire from Thiepval and the Schwaben Redoubt had resulted in heavy casualties.

Hamel had been costly, but not quite such a disaster as Richebourg. Casualties were high, the fighting strengths reduced further. But this was the Somme Battle, where any ground was paid for with a mighty price. And the Southdowns battalions had only just arrived.